It started with a formal apology.

“California Native American peoples suffered violence, discrimination and exploitation sanctioned by state government throughout its history,” California Gov. Gavin Newsom said in a 2019 statement. “We can never undo the wrongs inflicted on the peoples who have lived on this land that we now call California since time immemorial, but we can work together to build bridges, tell the truth about our past and begin to heal deep wounds.”

With that came an executive order to establish the California Truth and Healing Council for Native Americans “to clarify the record — and provide their historical perspective — on the troubled relationship between tribes and the state.”

The council’s work could set an example for the rest of the country.

There have been similar efforts internationally, in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. In the U.S., the Maine Wabanaki-State Truth and Reconciliation Commission examined harmful events relating to Wabanaki children and the Indian Child Welfare Act. There have also been instances of local governments giving land back to tribes.

But the California council, whose work is now underway, appears to be the first in the U.S. where a state is comprehensively looking to make reparations for the damage caused to its Indigenous communities.

The council is made up of 12 individuals from both federally and state-recognized tribes across California. Council members were nominated by tribes, but ultimately appointed by the state. There are more than 109 federally recognized tribes in California — and dozens more that are only state-recognized — so not every tribe has direct representation.

By 2025, the council must submit a report to the governor’s office that documents the full history of harm caused by the state. It will also make policy recommendations about reparations — which in this case may include land back and other ways to preserve California Native cultures — for past harm and prevention of further damage.

“We wanted to create a mechanism for tribes to be able to drive where the conversation was going,” said Christina Snider, Newsom’s tribal affairs secretary and a member of the Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians.

There have been similar efforts internationally, in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, but the council appears to be the first in the U.S. where a state is comprehensively looking to make reparations for the damage caused to its Indigenous communities. A similar panel was established in Maine in 2012, the Maine Wabanaki-State Truth and Reconciliation Commission, but it explicitly examined harmful events relating to Wabanaki children and the Indian Child Welfare Act. There have also been instances of local governments giving land back to tribes.

“We’re hopeful that giving Native people and tribes the time to think about what they really want from this process, what they want as a meaningful outcome, will be reflected in recommendations that are thoughtful and diverse and take equity into account,” Snider said.

She hopes to call private and federal partners to the table to work on solutions together once the final report is done. It would also fill huge gaps in many non-Indigenous Californians’ understanding of Native peoples’ history in the state, she said.

More than two years into the council’s listening sessions, interviews and research throughout the state, several issues have emerged, Snider said.

“A major theme here has been the idea of California Indian identity,” she said. “California Native people aren’t seeing themselves in the stories that are being told about Native people in general. Then their identity isn’t being translated into policy changes, either.”

The need for elder care, housing and mental health services have also come up frequently, Snider said. But there are also acute generational divides created in many communities by urbanization, boarding schools and other policies that separated Native families.

The council has also heard a lot of feedback around land — something Newsom’s administration is suggesting policies to address. In 2022, the state started providing funding to some tribes to co-manage parts of the coast.

Currently, Snider said, “there’s almost no access to land ownership and no access to places that are spiritually significant and where people have lived since time immemorial.”

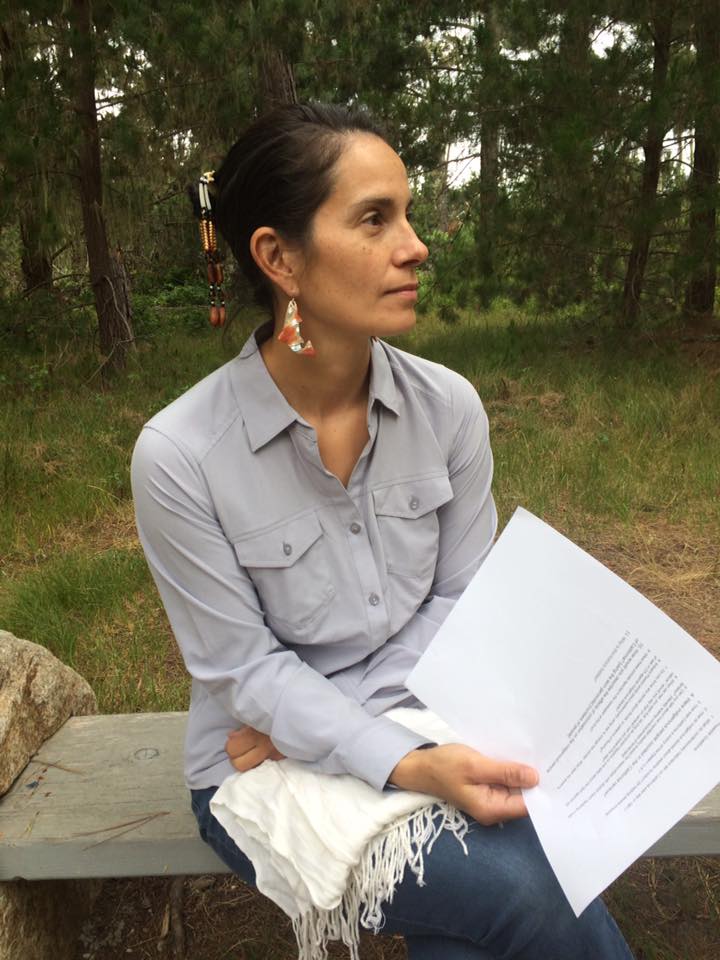

Kouslaa Kessler-Mata, a University of San Francisco associate professor and a member of the Truth and Healing Council and the Yak Tityu Tityu Northern Chumash and Yokut tribes, sees important work underway. But the infrequent meetings of the council and shortage of resources make her feel less empowered as a council member.

“I’m concerned about how the structure of the council is set up almost to position us as puppets,” Kessler-Mata said. “We’re not central to the process. We’re just there to help signify that something is happening, which is unfortunate.”

The council was set up through the state’s executive branch, rather than the legislature, where wide support and consensus is needed to pass initiatives. That means it has a more limited budget of only about $450,000 per year through the fiscal year ending in 2025, an annual amount roughly a third of what the legislature-established California Reparations Task Force for African Americans said it needed this year just for consultants to help with their work. The Truth and Healing Council also has fewer contracted researchers and staffers at the state dedicated to assisting the completion of its report when compared to the Reparations Task Force, Kessler-Mata said.

“A budget is a moral document,” Kessler-Mata said. “That absence of funding has serious consequential results in our work. We can’t achieve our objectives in a really thorough way without additional support.”

Snider said that creating the council through the executive branch meant it started faster and had more flexibility in its structure, developed after consultation with tribes. The result is that tribal leaders have more say in the process than they might otherwise, she said.

Some of the most important healing work from the process, Kessler-Mata said, has come through a partnership between the council and the Decolonizing Wealth Project, an Indigenous and Black-led organization that supports reparatory justice initiatives across the country.

In February, the Decolonizing Wealth Project awarded grants to 13 tribes and Indigenous organizations in California to help with initiatives aimed at healing and changing narratives about their history. The grants will help tribes collect oral histories, provide travel stipends for members to go to Truth and Healing Council meetings, fund work documenting impacts around boarding schools and more.

“When we heard this effort was happening in California, we knew it was important to support,” said Carlos Rojas Alvarez, director of executive affairs and strategic initiatives at the Decolonizing Wealth Project.

Alvarez said there has been a push for a federal commission to examine the full impacts of Native American boarding schools. Between 1819 and 1969, hundreds of thousands of Native American children were taken or coerced away from their families and tribes, forced to attend government-sanctioned Indian boarding schools. Among the consequences: loss of language and culture, abuse, trauma and permanent separation of many children from their families. Alvarez said he hopes the California effort will help drive momentum to address the boarding school history and related issues in other states and by the federal government.

The grants also help address a big challenge for the council: California Indians are a diverse group with different histories and needs.

“One Native person’s story in California is not the same as anyone else’s,” Snider said. “Each person has a different story, perspective and idea for what they need to make them whole.”

Some tribes involved in the process aren’t federally recognized, for example. And each tribe is a sovereign political entity. Kessler-Mata said she is one of the few council members who isn’t a tribal leader, which she feels is important because she doesn’t have a stake in any tribe’s enrollment battle or other political issues. Her goal is to stay focused on what the state can do “to advance the rights of individual Indians.”

Another challenge, Kessler-Mata said, is capturing a precise picture of the experience of California Indians. Most data on Native Americans in California is about all Native Americans who live in the state, regardless of whether they are members of a California tribe.

While the council’s final report won’t be finished until 2025, Kessler-Mata has early priorities. She wants to see the state start collecting data on California Indians to measure indicators like homeownership rates, impacts from climate change, educational outcomes and treatment in the criminal justice system. She also says the state needs to provide greater equity in funding for California Indians.

“What we really need is a multi-sector approach for people to understand what has happened and what is happening,” Kessler-Mata said. “The Golden State was created at the cost of someone else. That implicates everyone.”