WATERLOO, Iowa

Sheritta Stokes was worried, frustrated and determined to do something.

As schools sent children home to protect families from the coronavirus in 2020, she knew the students at her elementary school would feel an outsized impact. For the majority Black student body in this resource-starved part of town, normal was already a problem.

Stokes wasn’t the only Waterloo resident pondering how to change the status quo in a region that recently had been ranked the worst in the country for Black Americans. Some community leaders started an economic-empowerment organization, now running an accelerator providing support for Black business owners. One began working to launch a Black-owned bank.

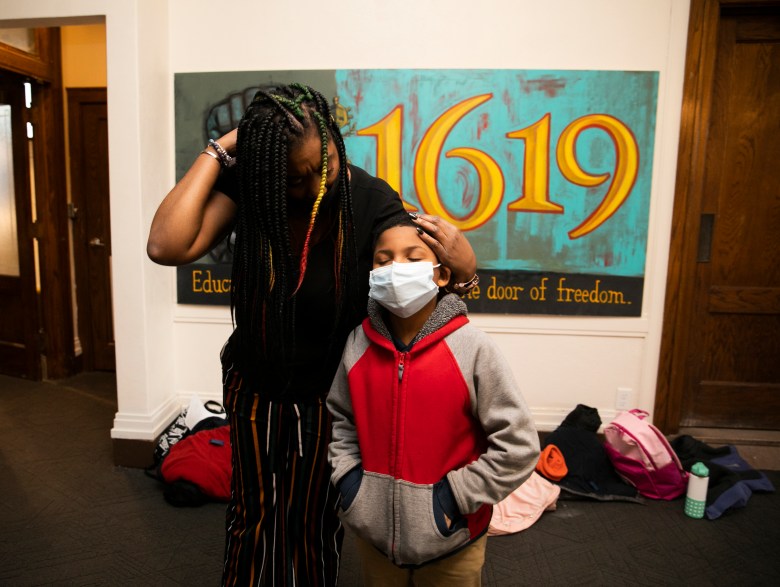

And Stokes? She and Waterloo native Nikole Hannah-Jones, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, teamed up to create an after-school literacy program inspired by the 1960s Freedom Schools of the civil-rights movement.

“I’ve been with the district for over 20 years, and for 20 years, we’ve been fighting to close the achievement gap,” said Stokes, a third-grade teacher at Waterloo’s Dr. Walter Cunningham School for Excellence. An entrenched disparity, she said, requires “doing something different.”

But as Hannah-Jones, Stokes and others began planning the 1619 Freedom School, surging racial-justice efforts nationwide were met with conservative white backlash — focused in part on American history and what students learn about it.

Since 2021, Republicans have introduced bills in roughly 40 states to restrict what schools can teach in class or cover in training, mostly related to race and often using language from an earlier Trump administration executive order, according to a PEN America tally.

Iowa passed a law that appears to ban curriculum and training about systemic racism, which educators say is having a chilling effect on frank discussions about both the past and present. A different bill proposed by a state legislator last year called for yanking funding from schools with lessons incorporating the 1619 Project, which was spearheaded by Hannah-Jones and places slavery and the Black experience at the center of the American story.

With all that as a backdrop, launching a free program for students that would embrace Black history and include “1619” in its name was no simple matter. Conversations with local grantmakers started strong, Stokes said, then largely fizzled amid the political furor.

Though the program has garnered some passionate support from local residents, “the majority of our funding came from out of state,” she said.

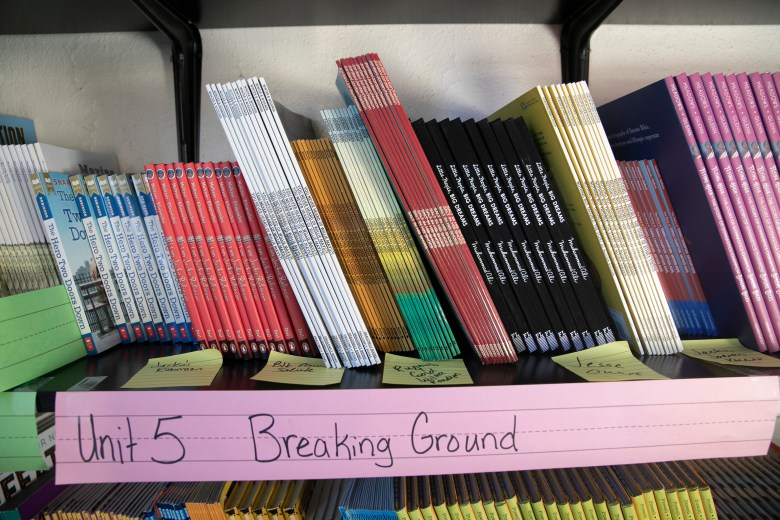

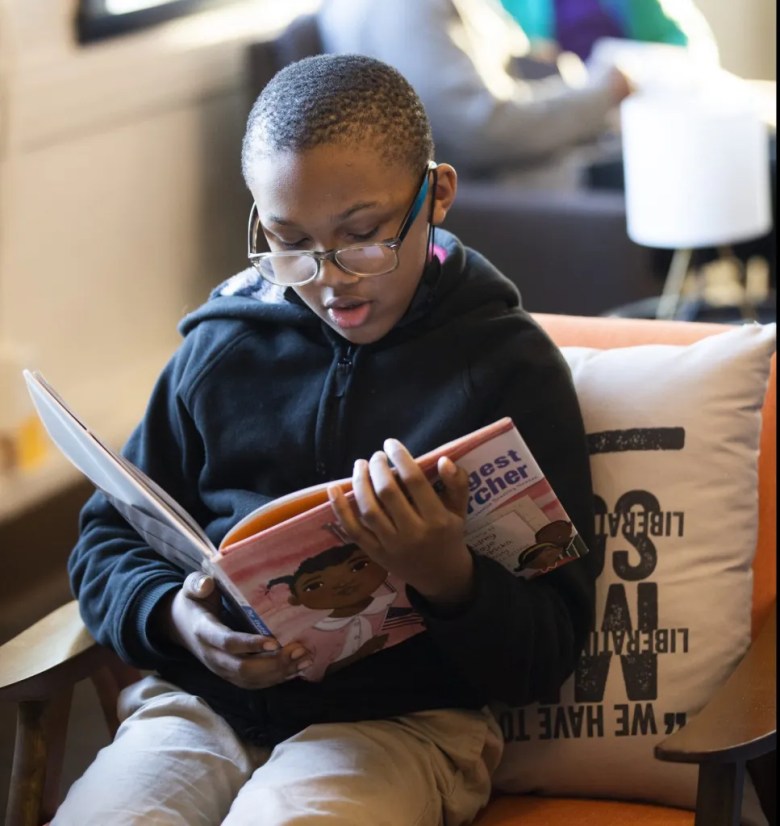

The 1619 Freedom School opened in January in a renovated Masonic Temple, an inviting space overflowing with books like The Youngest Marcher, walls decorated with colorful art and posters about the power of information. More than 30 fourth- and fifth-graders attend five days a week for two hours after school. The program provides literacy support and books to take home.

“So often our underserved communities get programs that are not well resourced,” Hannah-Jones said. “I think sometimes we think because we’re serving poor children and poor families, we don’t have to have the same type of quality that we do for other students. Everything about this program is trying to stand in opposition to that in saying, if our kids got the same resources, they obviously could achieve the same things.”

Building the literacy program around Black history also felt critical to the leadership team, which is largely made up of educators. They knew the impact that can have on achievement. And Hannah-Jones saw the difference it made in her own life.

“It changed my understanding of my place in the world,” she said. “It made me want to learn because I could see myself in the story.”

Lori Dale, a member of the program’s leadership team, said she’s heard some criticism about the 1619 Freedom School that seems to suggest “we’re trying to, I don’t know, start a revolution or something.”

“But in reality, it’s just to make sure our students, Black students in particular, are getting what they need,” said Dale, an educational counselor for Educational Talent Search at the University of Northern Iowa. “They are not getting what they need in the school district.”

In 2018, the financial news site 24/7 Wall St. tracked economic and social disparities between Black and white Americans in metro areas across the country and ranked Waterloo the most unequal. In more recent rankings, the area remained among the worst 10. White households in the city have 81 percent higher median incomes than Black households and more than double the homeownership rate, census data shows.

The past helps explain that present, just one reason decisions about how to teach history matter.

Local efforts to create or maintain segregation in Waterloo were underway since at least 1914, according to a University of Iowa project that tracked race restrictions in land records. The city was also among those redlined by the federal government in the 1930s, one of many ways that Black neighborhoods were blocked from mortgage lending and other investments.

Decades-old patterns of segregation still hang on today. Now they’re enforced not by law but by the economics of where people can afford to live — dictated by a racial wealth gap built up over generations of discrimination.

That plays out in Waterloo public schools. All three of the city schools that sit on land the federal government once redlined were rated below “acceptable” by the Iowa Department of Education in 2021, the Center for Public Integrity found.

Among the rest of the city’s schools, just roughly one-quarter have a less-than-acceptable rating.

Want more of The Heist?

Get behind-the-scenes info and alerts when new episodes become available.

Use the unsubscribe link in those emails to opt out at any time.

Nearly half the district’s Black students attend schools with such a rating, meanwhile, compared with a quarter of white students.

Many of the Waterloo schools in or near once-redlined places are helping children progress faster than the national average, according to a Stanford University analysis, but not enough to catch up.

“Waterloo is not an anomaly,” said Gabriel Rodriguez, an assistant professor of education at Iowa State University. Patterns like this are visible around the country, he said.

Part of what Rodriguez appreciates about the 1619 Freedom School approach is that its leaders see their students walking in with assets to build on, rather than deficits to fix.

“I think it’s exciting,” he said. “I think it’s awesome.”

Doing the work

In Waterloo, equity efforts are powered in large part by Black women.

Joy Briscoe, one of the 1619 Freedom School’s leaders, is also executive director of the 24/7 Black Leadership Advancement Consortium, which formed in 2020 and recently started the fourth round of businesses going through its accelerator program. Waterloo native Sharina Sallis is involved with both the school and consortium, too. And ReShonda Young, who runs the accelerator, is also working to launch the Bank of Jabez.

Briscoe said all 30 graduates of the accelerator are continuing to operate their businesses, despite the challenging pandemic environment, and some are growing. Her advice to anyone trying to improve their own communities: Focus on those most affected by the problem you’re trying to address. Center their voices. And, she said, team up with people “who are biased toward action. Don’t do a lot of meetings.”

Hannah-Jones, who said the 1619 Freedom School’s curriculum will be made freely available to anyone who wants to work on student literacy in their own area, would like more attention on the many regions like Waterloo: smaller Rust Belt places with Black communities locked out of the middle class.

She had the contacts to land out-of-town funding for the program, but most people trying to improve equity in their community don’t, she said.

“It just speaks to how challenging it can be,” Hannah-Jones said.

A key early funder of the 24/7 consortium was Red Cedar, a public-private partnership that helps startups in the region. Executive director Danny Laudick, who is white, said he’s noticed a hopeful shift in the last few years in how residents of the majority white city think about equity. More people are acknowledging that there’s work to be done, he said, and more are starting to do it.

“We have a responsibility to the people who are members of our community,” he said.

Quentin Hart is Waterloo’s first Black mayor. He was recently elected to his fourth two-year term after a challenge that tapped the anger of some white residents over his police chief’s decision to change a department logo reminiscent of a Ku Klux Klan symbol.

In a sign of pushback to the pushback, Waterloo residents elected a majority Black city council in November, refusing every candidate endorsed by a group that wanted the police logo back.

The city now evaluates decisions for their impact on equity, Hart said, and has been making investments in a redlined part of town. He’s delighted by the private efforts. What he wants is even more like that, from every part of the community.

“People need to acknowledge that there is a racial wealth gap, and whether directly or indirectly, you could be hurting or you could be helping,” Hart said. “We need to understand that we are all in this together, and it’s going to take all of us to be able to move the needle.”

It’s exactly that feeling of being in it together with others that makes Dale love Waterloo. The challenges are formidable. And yet she is not alone.

“I’m not saying it’s easy,” she said, “but I’m surrounded by people, positive people who are willing to do the work.”

You can hear a podcast about ReShonda Young’s quest to fight the wealth gap by opening a bank in the newest season of The Heist.